1 Process

The Site Development Process

Every significant web project poses unique challenges, but the overall process of developing a complex web site generally follows six major stages that you should think through before crafting your final project planning and proposal documents:

- Site definition and planning

- Information architecture

- Site design

- Site construction

- Site marketing

- Tracking, evaluation, and maintenance

Developing a large web site is a process that may have far-reaching budgetary, personnel, and public relations consequences for an organization, both during the development of the site and long after its deployment. Too many web sites begin life as ad hoc efforts, created by small interest groups working in isolation from their peers elsewhere in the organization and without fully considering the site’s goals within the context of the organization’s overall mission. The result of poorly planned, hasty development efforts often is an “orphan site,” starved of resources and attention.

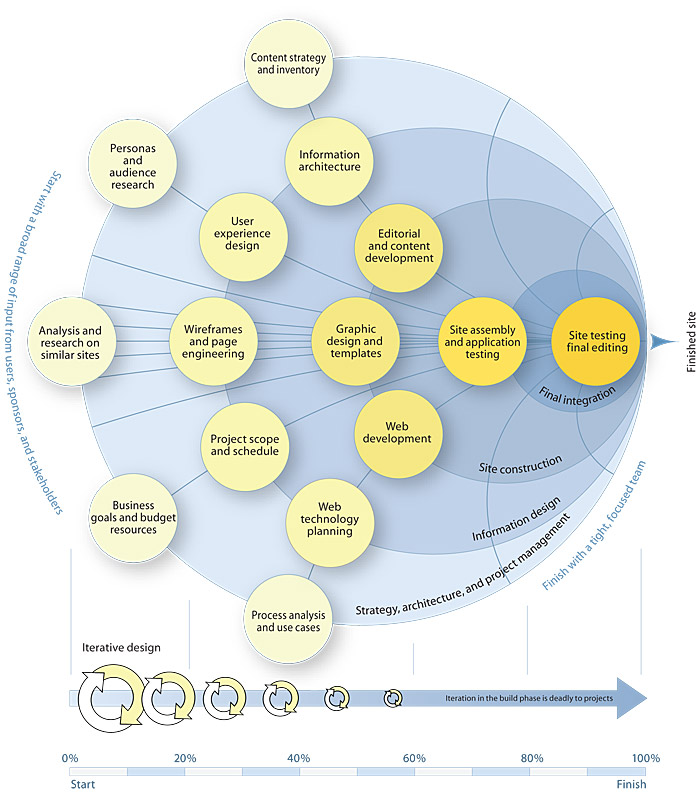

As you consider the development process outlined below, note that the construction of the pages that make up the web site is one of the last things that takes place in a well-designed project. Consider each step in the process and its impact on your developing project charter plan (see Developing a Project Charter, below). Think before you act, and make sure you have the organizational backing, budget, and personnel resources you’ll need to make the project a success (fig. 1.8).

Figure 1.8 — Another concept of web development projects, here emphasizing the necessary tightening of focus from broad input and participation in the beginning, to a narrow focused team at the end. Necessary, that is, if you ever want to finish your site on time and on budget.

Site definition and planning

This initial stage is where you define your goals and objectives for the web site and begin to collect and analyze the information you’ll need to justify the budget and resources required. This is also the time to define the scope of the site content, the interactive functionality and technology support required, and the depth and breadth of information resources that you will need to fill out the site and meet your users’ expectations. If you are contracting out the production of the web site, you will also need to interview and select a site design firm. Ideally, your site designers should be involved as soon as possible in the planning discussions.

Site production checklist

Not every site will require detailed consideration of every item on the lists below. Web teams within corporations or other large enterprises can often count on substantial in-house technology support when creating web sites. If you are on your own as an individual or small business, you may need to contract with various technology and design vendors to assemble everything you’ll need to create a substantial content site or small e-commerce site.

Production

- Will your site production team be composed of in-house people, outside contractors, or a mix of the two?

- Who will manage the process?

- Who are your primary content experts?

- Who will be the liaison to any outside contractors?

- Who will function long-term as the webmaster or site editor?

Technology

- What operating systems and browsers should your site support?

- What is the network bandwidth of the average site visitor?

- Will the site have dynamic html and advanced features?

- JavaScript required

- Java applets required

- Third-party browser plug-ins required

- Special features of the Linux, unix, or Microsoft iis server environments required

- Special security or confidentiality features required

- How will users reach support personnel?

- Email messages from users

- Chat rooms, forums, help desks, or phone support

- Does the site require database support?

- User logins required to enter any site areas

- Questionnaires required

- Search and retrieval from databases needed

- Will the site have audiovisual content?

- Video or audio productions

Web server support

- Will the site reside on an in-house web server or be outsourced to an Internet service provider for web hosting?

- Disk space limitations, site traffic limitations, extra costs

- Adequate capacity to meet site traffic demands

- Twenty-four-hour, seven-day-a-week support and maintenance

- Statistics on users and site traffic

- Server log analysis: in-house or outsourced

- Search engine suitable for your content

- cgi, programming, database middleware support

- Database support or coordination with in-house staff

Budgeting

- What are staffing costs?

- Short-term development staff

- Long-term editorial and support staff (site editor or webmaster)

- Ongoing server and technical support

- Database maintenance and support

- New content development and updating

- What hardware and software are needed for in-house development team members?

- What are staff training costs?

- Web use, database, web marketing, web design

- What are the outsourcing fees?

- Site design and development

- Technical consulting

- Database development

- Site marketing

Appoint a site editor to become the “process manager”

Every successful new web site makes a transition from a development project to an ongoing editorial process that keeps the site alive and fresh over time. You’ll need a project manager to get your new site launched, but you’ll also need to hand the site over to a process manager (read: “editor”) after the site is launched. A site that is “everyone’s responsibility” can quickly become an orphan. For current content and consistent editorial, graphic design, and management policies you’ll need one person to act as the editor of the overall web site. The site editor’s duties will vary according to how you choose to maintain your site. Some editors do all the work of maintaining site content, relieving their coworkers of the need to deal directly with web page editing. Other editors coordinate and edit the work of many contributors who work directly on the site pages, aided by a maintenance plan that specifies who is responsible for the content of each section of the site. When multiple people contribute to site maintenance, the site editor may choose to edit pages after they are created and posted to avoid becoming a bottleneck in the communications process. However, high-profile public pages or pages that contain important information should be vetted by the editor before posting. A site editor will also typically bear the primary responsibility for keeping the site content as visible as possible in local enterprise or general Internet search engines. Broken links and scrambled content organization schemes can harm your search engine rankings and make your content harder for users to locate. The site editor is also the logical person to handle the collection and analysis of web site analytics and to produce periodic reports on the usage of the site.

In addition to ensuring editorial quality, a site editor must also make certain that the content of the site reflects the policies of the enterprise, is consistent with local appropriate use policies, and does not contain material that violates copyright laws. Many people who post pictures, cartoons, audiovisual files, or written material copied from other sites on their own sites do not understand copyrights and the legal risks in using copyrighted materials inappropriately. A site editor is often an institution’s first line of defense against an expensive lawsuit over the misuse of protected material.

Information architecture

At this stage you need to detail the content and organization of the web site. The team should inventory all existing content, describe what new content is required, and define the organizational structure of the site. Once a content architecture has been sketched out, you should build small prototypes of parts of the site to test what it feels like to move around within the design. Site prototypes are useful for two reasons. First, they are the best way to test site navigation and develop the user interface. The prototypes should incorporate enough pages to assess accurately what it’s like to move from menus to content pages. These prototypes can be used to test the information architecture with users. Second, creating a prototype allows the graphic designers to develop relations between how the site looks and how the navigation interface supports the information design. The key to good prototyping is flexibility early on: the site prototypes should not be so complex or elaborate that the team becomes too invested in one design at the expense of exploring better alternatives.

Typical results or contract deliverables at the end of this stage include:

- Detailed site design specification

- Detailed description of site content

- Site maps, thumbnails, outlines, tables of contents

- User-tested wireframes and prototypes demonstrating site architecture

- Multiple graphic design and interface design sketches

- Detailed technical support specification

- Browser technology supported

- Connection speed supported

- Web server and server resources

- Proposals to create programming or technology to support specific features of the site

- A schedule for implementing the site design and construction

Site design

At this stage the project acquires its look and feel, as the page grid, page design, and overall graphic design standards are created and approved. Now the illustrations, photography, and other graphic or audiovisual content for the site need to be commissioned and created. Research, writing, organizing, assembling, and editing the site’s text content is also performed at this stage. Any programming, database design and data entry, and search engine design should be well under way by now. The goal is to produce all the content components and functional programming and have them ready for the final production stage: the construction of the actual web site pages.

Typical products or deliverables at the end of this stage include:

Content components, detailed organization and assembly

- Text, edited and proofread

- Graphic design specifications for all page types

- Finished interface graphics for page templates

- Header and footer graphics, logos, buttons, backgrounds

- Detailed page comps or finished examples of key pages

- Site graphic standards manual for large, complex sites

- Interface design and master page grid templates completed

- Finished html template pages

- Illustrations

- Photography

Functional and logic components

- JavaScript scripts, Java applets designed

- Database tables and programming, interaction prototypes completed

- Search engine designed and tested

Templates

Whether you develop your site on your own or hire a professional web developer, you should develop page templates for your new web site. It’s much easier to add new pages when you can start from a page that already contains basic navigation and site graphics. If you have a team working on page development, you will want to share templates, along with standards on how to handle page text and content graphics. Popular web site development software such as Adobe Dreamweaver offer powerful templates and standard reusable libraries of site graphics and html that make it easy to create new pages and maintain consistency in your site.

Accessibility

In most large enterprises, providing universal access to web pages is long-established institutional policy, and in many instances it is required by state or federal regulations. It is critical, therefore, that you validate your designs and page templates and the content of your site throughout the development process to ensure that your pages are accessible to all users. Use the guidelines and techniques developed and maintained by the Web Accessibility Initiative (wai) as a measure against which to test the accessibility of your pages.

Site construction

Only at this mature stage of the project are the bulk of the site’s web pages constructed and filled out with content. By waiting until you have a detailed site architecture, mature content components, fully tested wireframes and prototypes, and a polished page design specification you will minimize the content churning, redundant development efforts, and wasted energy that inevitably result from rushing to create pages too soon. Of course, you will always learn new things about your overall design as the prototype matures into the full-blown web site. Be prepared to refine your designs as you and your users navigate through the growing web site and discover both weak spots and opportunities to improve navigation or content.

Once the site has been constructed, with all pages completed and all database and programming components linked, it is ready for user testing. Testing should be done primarily by people outside your site development team who are willing to supply informed criticism and report programming bugs, note typographic errors, and critique the overall design and effectiveness of the site. Fresh users will inevitably notice things that you and your development team have overlooked. Only after the site has been thoroughly tested and refined should you begin to publicize the url of the site to a larger audience.

Typical products or deliverables at the end of this stage should include:

- Finished html for all web pages, all page content in place

- Finished navigation link structure

- All programming in place and linked to pages, ready for user testing

- All database components in place and linked to site pages

- All graphic design, illustration, and photography in place

- Final proofreading of all site content

- Detailed testing of database and programming functionality

- Testing and verification of database reporting features

- Testing of site user support procedures, answering email, etc.

- Archives of all site content components, html code, programming code, and any other site development materials

Maintainable code

Most businesses or departments in larger enterprises will contract with a web development group to create the initial site design and to build all the pages in the first version of the web site. They then assume responsibility for the site, doing some or all of the daily maintenance and updating content as needed to keep the site current.

Often not until the practicalities of site maintenance arise do customers realize the importance of understanding the details of how the web developer generated the html and other code that makes up the web site. Although all html and css markup is much the same to web browsing software, how the html and css is formatted and what web authoring tool the developer used can make a huge difference in how the code looks to a human reader.

Consider the two code examples below:

Example 1

<table summary=”HR Committee Schedule, FY 2008”>

<tr>

<th>Meeting Dates 2008</th>

<th>Agenda Item Submission Deadline</th>

</tr>

<tr>

<td>Monday, Oct 6, 2008</td>

<td>Friday, Oct 3, 2008</td>

</tr>

</table>

Example 2

<table summary="HR Committee Schedule, FY 2008"> <tr> <th>Meeting Dates 2008</th> <th>Agenda Item Submission Deadline</th> </tr> <tr> <td>Monday, Oct 6, 2008</td> <td>Friday, Oct 3, 2008</td> </tr> </table>

Which example do you find easier to understand? These code examples are exactly equivalent to a web browser, but most people would find Example 1 significantly easier to read and understand. If you contract with a developer to build your site, it is important to understand how the developer writes code, what state the code will be in when the site is delivered, and whether the software used by the developer is compatible with what you will be using to maintain the site after delivery. Some web development software produces html code that is nearly impossible for a human to read without significant (and expensive) reformatting. Other programs (such as Adobe Dreamweaver) produce html code that is easy for web programmers to read, which can make a huge difference if you decide to change web developers or if you decide to edit html directly when maintaining your site.

If you hire someone to create your web site or components of your site, such as database or dynamic elements, be sure to ask what tools they will use to write the html and any other code. Ask to see examples of code written for other clients. Have your technology lead examine the code to be sure the developer inserts explanatory comments and dividers for legibility in the code. Be sure to find out whether there will be problems or conflicts if you use your favorite tools to edit the code the developer produces. Make sure the developer understands what editing tools you prefer to use and develops the code for maximum compatibility with your maintenance tools.

HTML and CSS code validation

Also ask for representative sites the developer has created, and choose pages to test for code validity, using the free online tools available from the w3c (see below). Many perfectly functional pages will fail w3c validity tests either for relatively minor code mistakes or for complex links to database or application urls that use problematic characters like ampersands (&). Ignore minor failures in the code validation, since they are unlikely to cause major functional problems. But if representative pages come back from testing with long lists of html code problems and css mistakes, beware of that developer’s work, and thoroughly discuss and put in writing your expectations around code validation as part of any contract.

html and css code validation tools from the w3c:

- html validation: validator.w3.org

- css validation: jigsaw.w3.org/css-validator

Today’s web pages are much more complex than pages in the past, and many new mobile and other devices can now display web pages. Search visibility is crucial to successful web sites, and web accessibility is a legal requirement with a growing set of case law behind it. Using carefully validated html and css code is one of your best strategies for getting maximum flexibility and value from your web development dollars. Be extremely wary of a web developer who tells you, “Validation isn’t important.”

Site marketing

Your web site should be an integral part of all marketing campaigns and corporate communications programs, and the url for your site should appear on every piece of correspondence and marketing collateral your organization generates.

If your web site is aimed primarily at local audiences you must look beyond getting listed in standard web indexes, such as Yahoo! and Google, and publicize your url where local residents or businesses will encounter it. Local libraries, newspapers, and schools are often the key to publicizing a new web site within a specific locale.

You may also find opportunities to cross-promote your site with affiliated businesses, professional organizations, broadcast or print media, visitor or local information agencies, real estate and relocation services, Internet access providers, and local city or town directory sites. Your organization could also feature local nonprofit charitable or school events on your web site. The cost in server space is usually trivial, and highly publicized local events featuring a web page hosted within your site will boost local awareness of your web presence. Site sponsorship might also interest local broadcast media as an interesting story angle.

Your home page url should appear in all:

- Print advertisements

- Radio and television advertisements

- Lobby kiosks in high-traffic areas of your enterprise or in local libraries, schools, or other suitable venues

- Direct mail campaigns

- Business cards

- Stationery

- Bills and statements

- Product manuals and product packaging

- Response cards and warrantee cards

- Publications and promotional materials

- Press releases

- Posters and billboards

Tracking, evaluation, and maintenance

Your web server software can record an abundance of information about visitors to your site. Even the simplest site logs track how many people (unique visitors) saw your site over a given time, how many pages were requested for viewing, and many other variables. By analyzing the server logs for your web site you can develop quantitative data on the success of your site. The logs will tell you which pages were the most popular and what brands and versions of web browser people used to view your site. Server logs can also give you information on the geographic location of your site users. Detailed logs are the key to quantifying the success of a web site. Your webmaster should archive all site logs for long-term analysis and should be prepared to add or change the information categories being logged as your needs and interests change.

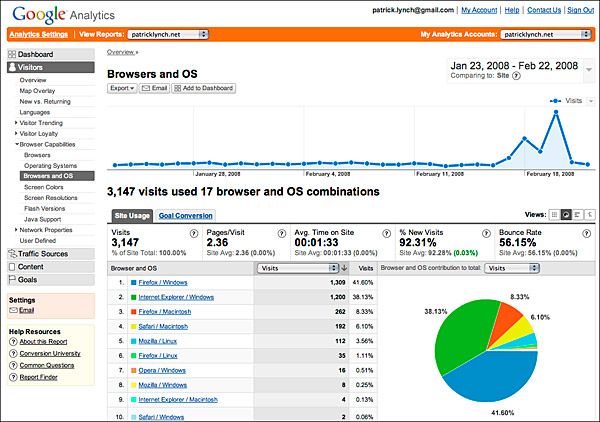

A number of popular software packages are designed to produce easily readable site traffic reports, complete with data graphics and charts to aid in data analysis. As a service to customers, site hosting companies often offer reports from popular site analysis programs like Google Analytics for no additional charge. Before contracting with an Internet service provider for site hosting services, always ask about site analysis services. If your isp (Internet service provider) or corporate web site does not offer a good site traffic analysis package, ask whether the webmaster can give you access to a monthly server log of your account. Basic versions of traffic analysis programs like WebTrends are inexpensive and you can run them on a personal computer if you can gain access to the raw web server log from your isp or corporate webmaster (fig. 1.9).

Figure 1.9 — Web statistics are much more than just raw measures of traffic. They can tell you what content people looked at, where your visitors are coming from, and provide a rich set of technical information on what technology your typical readers are using. From Google Analytics.

Maintaining the site

Don’t abandon your site once the production “goes live” and the launch parties are over. The aesthetic and functional aspects of a large web site need constant attention and grooming, particularly if a group of individuals shares responsibility for updating content. Your site editor will need to be responsible for coordinating and vetting the new content stream, maintaining the graphic and editorial standards, and ensuring that the programming and linkages of all pages remain intact and functional. Links on the web are perishable, and you’ll need to check periodically that links to pages outside your immediate site are still working. Don’t let your site go stale by starving it of resources just as you begin to develop an audience—if you disappoint them by not following through, it will be doubly difficult to attract your audience back to the site.

Backups and site archives

The site editor should be sure that the web site is regularly backed up onto a secure and reliable storage medium to ensure that a catastrophic hardware failure in your web server does not wipe out your web site. Most web servers maintained by it professionals or commercial web service providers are backed up at least once a day. If you don’t know what your backup schedule is, ask your webmaster or web hosting provider. Human error is the most common reason you may need quick access to a backup copy of your web site. Unfortunately, it’s easy to overwrite an old file (or a whole directory of files) accidentally over a newer version on the web server, to delete something important in error, or to wipe out someone else’s work by mistake when updating a web site. A recent backup (ideally no more than twenty-four hours old) can often be a lifesaver.

If your site is successful, it will quickly become an important record of your enterprise’s work, your accomplishments, and a valuable record of the “state of things” as the site evolves over time (fig. 1.10). Unfortunately, too little attention is paid to this aspect of web sites, and we are collectively losing huge pieces of our hig because no one thinks about preserving permanent records of a web site. Unless your web site is prohibitively large, your web site editor should arrange to collect and store the files of the site periodically or contract with your web service provider to set aside a backup version at regular intervals as a long-term archive. We take for granted the “paper trail” of history left by conventional business and work practices. Without a plan for preserving our digital works, our collective history may vanish without a trace.

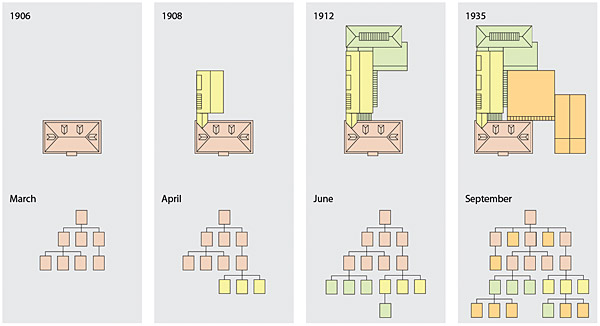

Figure 1.10 — Much as older buildings grow through additions and adaptation over time, sites grow and change in response to changing needs and ideas. (Adapted from Stewart Brand’s How Buildings Learn.)