2 Universal Usability

Universal Usability Guidelines

Human-computer interaction (hci) pioneer Ben Shneiderman defines universal usability as “having more than 90% of all households as successful users of information and communications services at least once a week.” Note that Shneiderman is not calling for any use of technology but rather successful use. He goes on to explain that, to achieve universal usability, designers need to “support a wide range of technologies, to accommodate diverse users, and to help users bridge the gap between what they know and what they need to know.”

It’s important to think about universal usability as a goal and not an outcome. Clearly, no web site can accommodate every possible use context, any more than a potato peeler can be used successfully by every individual. The web provides an environment that is far more flexible than the built world, making the goal of universal access more feasible.

Moving beyond the “typical” user

The first step toward the goal of universal usability is to discard the notion that we are designing for a “typical” user. Universal usability accounts for users of all ages, experience levels, and physical or sensory limitations. Users also vary widely in their technical circumstances: in screen size, network speed, browser versions, and specialized software such as screen readers for the visually impaired. Each of us inhabits multiple points on the spectrum, points that are constantly shifting as our needs and contexts change. For example, virtually all adults over fifty have some form of mild to moderate visual impairment. And within that context our needs change as we move from viewing web pages from the back of an auditorium to sitting in front of a large desktop display monitor to walking down the street peering at a small mobile display. A broad user definition that includes the full range of user needs and contexts is the first step in producing universally usable designs.

Supporting adaptation

Next we need a design approach that will accommodate the diversity of our user base, and here we turn to the principle of adaptation. On the web, universal usability is achieved through adaptive design, where documents transform to accommodate different user needs and contexts. Adaptive design is the means by which we support a wide range of technologies and diverse users. The following guidelines support adaptation.

Flexibility

Universal usability is difficult to achieve in a physical environment, where certain parameters are necessarily “locked in.” It would be difficult to make a book, and a chair to read it in, that fit the needs and preferences of every reader. The digital environment is another story. Digital documents can adapt to different access devices and user needs based on the requirements of the context.

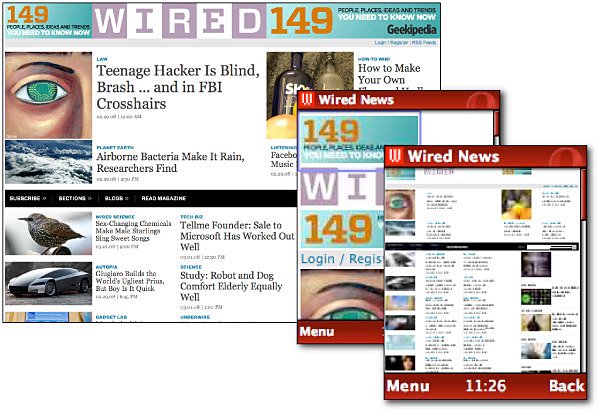

A web page contains text, with pointers to other types of documents, such as images and video. Software reads the page and acts on it by, for example, displaying the page visually in the browser. But because of the nature of the web, the same page can be accessed on a cell phone, using a screen reader, or printed on paper. The success of this adaptation depends on whether the page design supports flexibility. Pages designed exclusively for large displays will not display well on the small screens of cell phones (fig. 2.1).

Figure 2.1 — Page designs optimized for screen displays don’t always fare well on mobile devices.

The web environment is flexible, with source documents that adapt to different contexts. When considering universal usability, we need to anticipate diversity and build flexible pages that adapt gracefully to a wide variety of displays and user needs.

User control

In many design fields, designers make choices that give shape to a thing, and these choices, particularly in a fixed environment, are bound to exclude some users. No one text size will be readable by all readers, but the book designer must make a decision about what size to set text, and that decision is likely to produce text that is too small for some readers. In the web environment, users have control over their environment. Users can manipulate browser settings to display text at a size that they find comfortable for reading.

Flexibility paired with user control allows users to take control of their web experience and shape it into a form that works within their use context.

Keyboard functionality

Universal usability is not just about access to information. Another crucial component is interaction, in which users navigate and interact with links, forms, and other elements of the web interface. For universal usability, these actionable elements must be workable from the keyboard. Many users cannot use a mouse, and many devices do not support point-and-click interaction. For example, nonvisual users cannot see the screen, and many mobile devices only support keyboard navigation. Some users use software or other input devices that only work by activating keyboard commands. For these users, elements that can only be activated using a mouse are inaccessible.

Make actionable elements workable via the keyboard to ensure that the interactivity of the web is accessible to the broadest spectrum of users.

Text equivalents

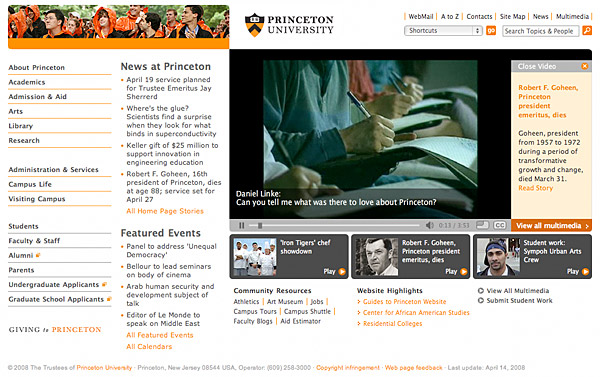

Text is universally accessible. (Whether text is universally comprehensible is another discussion!) Unlike images and media, text is readable by software and can be rendered in different formats and acted upon by software. When information is presented in a format other than text, such as visually using images or video or audibly using spoken audio, the information is potentially lost on users who cannot see or hear. Web technology anticipates format-related access issues and supplies methods for providing equivalent text. With equivalent text, the information contained in the media is also available as text, such as a text transcript or captions along with spoken audio (fig. 2.2).

Text equivalents allow universal usability to exist in a media-rich environment by carrying information to users who cannot access information in a given format.

Figure 2.2 — Equivalent text for spoken audio in the form of captions.